"Misunderstanding innovation, we create systems that inhibit randomness and the beauty of serendipity"

- A Conversation with Aaron Dignan, founder of The Ready

- The Sixth Floor

- Innovation

'I don’t think we can solve the macro problems on the level of the political system, the environment or inequality without going in the direction of more participation and more autonomy,' Aaron Dignan says. 'In the near future, the world of work might be dominated by automated, extractive global organizations that look like Amazon, but create almost no vibrancy in the ecosystem. Or we might return to our roots in terms of cooperatives and employee-owned organizations, moving back to an environment where we try to create sustainable, local success. To me, that is the battle of our time. What I would like to see is more autonomy, more transparency, more participation.'

In this episode of 'The Sixth Floor', CFO Services Jean-Marie Bequevort and Dirk van Bastelaere have a conversation with Aaron Dignan, founder of The Ready, a New York based consulting company specialized in organizational design that helps institutions like Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Citibank, Airbnb and the Smithsonian Design Museum. Aaron is also a cofounder of responsive.org, an angel investor in purpose-driven startups.

With The Ready, Aaron Dignan helps organizations become more adaptive, reinventing their operating system. A necessary thing. 'Almost every legacy organization, government, and municipality in the world has the same problem,' Aaron said in an earlier interview. 'Their operating model -- the way they make decisions, hire and fire, structure, build and test products -- is built like the bureaucratic administrative complex of yesteryear. It’s based on command and control, on authority, rigidity, scale and stability.'

Aaron Dignan is the author of two books: Game Frame: Using Games as a Strategy for Success (2014) and Brave New Work, a complexity-conscious, people-positive book that explains how organizations can move away from command-and-control bureaucracy towards diversity, autonomy and empowerment. It will be out in February 2019. Aaron Dignan will be on tour in Europe, presenting the book during workshops in London, Paris and Amsterdam.

In this talk, Aaron addresses issues like adaptivity at scale, participatory change, reinventing the operating system, risk management, bureaucracy and organizational debt.

Interview by Jean-Marie Bequevort and Dirk van Bastelaere

Forests, anti-fragility, neurons and adaptivity at scale

Jean-Marie Bequevort: Aaron, can you shed some light on your background and what led to you founding The Ready?

Aaron Dignan: ‘I found my way to this work circuitously. When I came out of school, I was mainly thinking about psychology of brands and psychology of cults. I was fascinated about why people feel irrationally connected to different communities, memberships and brands that basically build their identity.

‘So, I worked on brand strategy and brand experience for several years. I started to notice that brands that were shaping culture most readily were digital brands like Google, Apple and Facebook. I became curious about this. With some friends I started a company called Undercurrent, focused on digital disruption. We set up this company because we wanted to consult important institutions about the ways exponential and disruptive technologies might change their business landscape. Look at how 3D printing now affects the supply chain in GE aviation. Also, we looked at what we can do for the industry with added manufacturing, combined with crowdsourcing or remote workforces.

‘We did a lot of business in digital strategy, going from artificial intelligence to robotics, social media and big data. We advised a lot of big companies like GE and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Talking to executive leaders, we found everybody agreed on what was disrupting, they only could not do anything about it.

‘As an example, you could have a project with 25 000% ROI in 3D manufacturing and the next quarter do zero projects like that. The incentives, the quarterly targets, the structures and silos were getting in the way, making it impossible for organizations to adapt and take advantage of market forces.

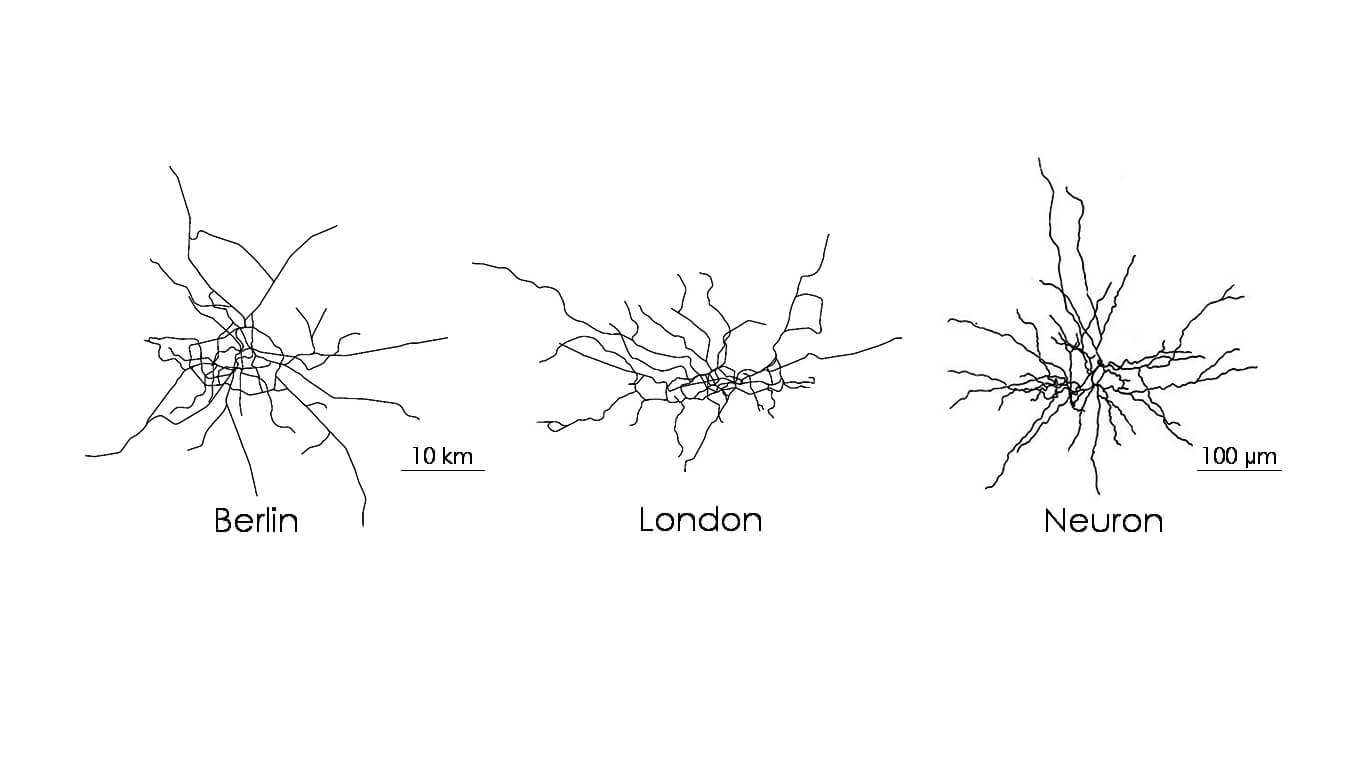

‘I became curious about adaptivity at scale: what does it look like to have scale systems that can learn. Is it possible, where is that happening and what can be taken away from this? Once again, I took the leap and followed my curiosity into this space of self-organization. I looked at biomimicry and anti-fragility. Also, I looked at companies on the edge of culture that were doing things differently, looked at complex adaptive systems, like neurons and immune systems, forests, birds. You name it! (laughter).

'The conclusion I drew was that adaptivity and the agility at scale is possible. It is happening in companies around the world, but it requires a very different mindset and a very different set of practices and principles than we are used to. You could see hints of that in words like agile and lean, and in new ways of working. However, there was not really a movement yet to bring it all together and I saw this as the next frontier. So, I started up The Ready.’

Resistance to change

Jean-Marie Bequevort: With your work on digital you were confronted with resistance to change and adaption in big organizations. What exactly do you do at the Ready to help companies adjust, or at least increase their fitness for change?

Aaron Dignan (chuckles): ‘What we have learned is that, when you have these huge, complex human systems, the wrong way to do change is to mandate it from the top-down. It’s not that you never need decisiveness or clarity about where you are going. The behaviors we are looking for really require participation.

‘So, we bring about change “by invitation”. We go in, we expose people to the time and space to think about their work. It is important to ask them: “What is stopping you from doing the best work of your life?”. Whatever the answer to that question is, is where you should start. Causes can vary: “The budgeting process is taking 9 months of the year!”, “My manager does not trust me!”. This allows us to define the issue: a trust issue, resource allocation issues or communication issues. We follow the curiosity and we follow the tension into change. When we invite people to work on the things that hold them back, it is amazing how excited they are to engage and start moving.’

Defining the playground

Jean-Marie Bequevort: What exactly is your approach then? Do get better results by working at the individual level or do you work at the level of the leadership trying to stimulate change that would trickle down the organization?

Aaron Dignan: ‘We don’t spend a lot of time one-on-one. We are often invited by a leader or by someone who is frustrated and has power. They might be frustrated with the bureaucracy or the slowness of it all. We will say: “Where can we play?”. We actually define a playground. Within that team of teams, within this function or location, we have free range to reinvent the operating system with the team and for the team. Then, we work both with the leadership group of that sphere as well as everyone inside. It is about choosing the field of play. We always work with teams. This allows us to let the teams work better because the team is the unit of performance at the end of the day.’

Jean-Marie Bequevort: So, you introduce the change by showing people they are participants in the change trajectory?

Aaron Dignan: ‘Absolutely. People can opt out. We make sure people get the time to think about the idea. We might bring 6000 people through an experience where they get a chance to stop and think about the way they work. It is important to let them reflect on how their job is serving or not serving them. At the end we ask who wants to ‘play’? People raising their hand can immediately start playing. If not, they don’t have to play. Often, they might come around later when they realize that what we try to do is not impose but rather make space for them to upgrade the way they are working. The Ready just starts with the invitation once everyone has had the time to stop and think.’

The edge is where emergent progress can occur

Dirk van Bastelaere: I can very well imagine that you have certain people in certain divisions wanting to embark on a change trajectory when you guys enter the scene. But where do you hit the limits of what is possible? Looming beyond the project, there most certainly is this huge Leviathan of an organization that often cannot deal with change the way you have introduced it in the division or smaller unit.

Aaron Dignan (amused): ‘That happens all the time, and I actually think it can be a feature or a bug. It depends on the culture. The feature part is that everybody can smell it or feel it when we get something going in a function or a division. They sense the difference, the speed, the engagement. While we get stress and friction in the early days when we engage with other groups, in the later days we get a lot more curiosity. Right now, we are doing a project with a global organization. We started the project in global marketing. A year later, people from finance and operations are wondering if they should step in too.

‘The edge is where emergent progress can occur. We think hard about that phenomenon. We try to invite people in early and often, just to explain what we are doing and why we are doing it. When it’s going well, it’s creating natural spread and when its going poorly it’s usually because we are not doing well enough inside the group. When you have something magical going on, the natural momentum creates curiosity and spread, even if it is a little disruptive. But I have seen it both ways and I have been frustrated many times by reactions of other functions.’

Continuous participatory change

Dirk van Bastelaere: Can corporations eventually deal with the heterogeneity that you are creating? You introduce change in one part of the organization, but other parts probably keep functioning in a more traditional way. Isn't that meant to happen when you guys come in?

Aaron Dignan: ‘Some things need to be system-wide for the system to be healthy and successful. You don’t want to have five hundred different data strategies. But there are a lot of things that we can allow more divergence on and more local relevance. Organizations generally have this untested belief that monoculture and singular approaches is how we get scale and efficiency. People all have to do it one way, because that is the way it is done. That gives us efficiency. Effectiveness, however, can come from different approaches. As does learning.

A company like Handelsbanken in Sweden has hundreds of branches, but they have some standard spaces that they govern collectively around data, privacy, communication and measuring and rewarding success. The local branches on the other hand have a ton of autonomy. What is cool about that, if a branch starts to blow the numbers out of the water, the other branches will start to analyze what the successful branch is doing differently. They will learn from each other, because they are incentivized for collective success.

‘It is always a balancing act, but that kind of divergence you are talking about is just temporally. It will either end in the groups that have not changed the way they work, changing the way they work over time or it will end in the company going out of business. The only thing we ask, by the way, is that an organization introduces continuous participatory change. We won’t ask anybody to go 100 percent transparent or 100 percent employee-owned.

‘If that is true, then you are done. As from now, you live in a state of continuous consideration, asking: “What is the biggest tension now?” “What is holding us back now?”

The beauty of serendipity

Dirk van Bastelaere: Great example of how decentralization has a positive effect on innovation. Because hierarchy has proven to be rather bad for innovation.

Aaron Dignan: ‘Totally. There is a fundamental misunderstanding about innovation and evolution. Some people think innovation will happen because the leader has a big idea. That is not how it happens. So much of the modern world is the result of accidents.

The microwave exists because someone had a candy bar in their pocket that melted when they were working with that technology. Play Doh was supposed to be a wallpaper cleaner and now it is a popular child’s toy. Airbnb was just three guys that said, we have an extra room and no rent this month. We put an air mattress in the living room and make rent. It was not a 33-billion-dollar idea. It was guys trying to make rent. When we misunderstand that, we create systems that really inhibit that randomness and the beauty of serendipity.

The lighted intersection vs. the roundabout

Jean-Marie Bequevort: What to you are the major flaws of today’s corporate structure or corporate operating systems? What is wrong with the way organizations are working today?

Aaron Dignan (laughs): ‘It is a long list! There are 78 tensions we write about in the book. At the pinnacle of it all, is the general sense that people cannot be trusted to do good work or make good decisions. So, we must protect people from themselves and protect the organization from its people through compliance, regulation and hierarchy.

‘I use the metaphor of the lighted intersection versus the roundabout. The lighted intersection assumes that no one can be trusted and uses the authority of the traffic light to tell you when to go and when to stay. Everybody is compliant. The roundabout assumes trust and responsibility, using only 2 simple rules: “Go into the direction of traffic” and “Give right of way to people in the circle”.‘On almost every measure like throughput, safety, fatalities, collisions, cost to build and maintain, … the roundabout is superior. But if you ask every person in the world on what is safer and what they prefer, they prefer the controlled environment of the lighted intersection.

‘I think that is a metaphor for everything that is happening at work and every practice from the way we budget and structure to the way we write policies, develop people, review people, we have a lot of lighted intersections at work, instead of roundabouts. As a result, we have accountability rather than responsibility, compliance rather than creativity. This does not mean that every intersection in the world should be a roundabout. If you did that in downtown Manhattan, it would be a disaster, there would be no room for the buildings.’

Risk management and the need for divergence

Jean-Marie Bequevort: If you would be an internal auditor, how would you balance risk versus the way people work?

Aaron Dignan: ‘It all starts with principles: what do we believe to be true about what will make us most competitive? Imagine we are an organization where people believe that transparency, information symmetry, and the fact that everybody has access to the information that matters for good decisions are important. We are then going to make choices about how we share information and where we can get information as employees that creates risk. Cases might arise where bad actors take information and put it where it doesn’t belong or just do things with it they are not supposed to do. The question to ask is: “Is the fact that one percent of the people does something wrong with the information sufficient risk to outweigh the risk of not being a company that has transparency and makes decisions effectively and where everyone has the information they need to be intelligent?

‘I always look at the risk of acting versus the risk of not acting. I want to balance the equation more than the typical kind of risk management theory might suggest. Following those theories, you would look at what can go wrong and how you can stop it. If that is your view on the elimination of risk, the best way to avoid it is to close your doors and shut the business down. Companies with that kind of low-risk mentality, however, will be outmoded by a new competitor who is willing to take risks in order do find solutions.’

‘There are plenty of precedents for this in biology, were we just look in ratios of risk to reward and random behavior. There always has to be divergence. There always has to be randomness, variation, mutation in order for a system to evolve.

The dangerous 5 percent

'I think you are always just weighing things as a risk manager, asking: “What is the risk of not acting?”; “What is the risk of not sharing versus the risk of sharing?” or “How do we create punitive measures that are very targeting.” At Google, if someone spills the beans from their TGIF (Thank God it’s Friday) meeting on Friday, were they share really important strategic things, that person is fired. Immediately, and publicly. But they do not shut down the meeting. They do not stop telling everybody what is going on.

‘Organizations tend to develop scar tissue around every error. I think we need to design for the 95 percent of scenarios that develop and not for the dangerous 5 percent, unless those 5 percent scenarios are the ones that can literally kill your organization.

‘Companies often use a “safe-to-try” approach to evaluate things, asking if certain decisions or situations will be reversible or irreversible. Jeff Bezos talks about that at Amazon a lot. There it’s called “Type 1 and Type 2 decisions”. If this goes wrong, can we turn back or not. Some things are irreversible, but the vast majority of things in business are totally reversible. Especially, when you are big. If you are a billion-dollar company, you can blow a million bucks and it is okay. That is just my general thesis.’

Jean-Marie Bequevort: What we see at some of our customers is that, when there is a lack of clarity on the impact of a decision, policies are applied that frame the conversation.

Aaron Dignan: ‘Absolutely. It becomes dangerous when people that are functionally obligated to eliminate risk and who are not beholden to a broader, creative, generative mission, will say “No” to daring initiatives, because I am always going to say “No” if that is my job. This is where functions become dangerous.’

Chesterton's fence

Jean-Marie Bequevort: Recently, we have been exploring the field of complexity in organizations. We found out that more people from the public sector were unsatisfied with the complexity and efficiency of their organization than employees in the private sector. Sounds kind of trite, but do you have a particular perspective on the difference between government institutions and private companies?

Aaron Dignan: ‘Absolutely. One of the things that is very true about all organisms, from organizations to bacteria, is that the environment in which they exist creates conditions that shape them. If you look at public-sector work and public-sector organizations, they are generally immune to environmental change. They are not affected as severely, as quickly, as meaningfully as a private sector organization is. If the world turns, you are not going to get rid of the postal service just because email came out. It is a long slow death. The result is that bureaucracy creeps in and there is no real motivation, no urgency to address it or refactor it. So, you get that additive organizational layer upon layer upon layer. There’s also this issue in the public sector of rotational, election-based, cycle-based membership. You have people cycling in and out of roles, who don’t necessarily have the information of the people before them.

‘The impact of that knowledge gap can be explained by the Chesterson's fence parable, where people come upon a fence in the middle of nowhere and see the fence is not holding anything. They look at it, wondering: “What is that fence for?” They weren't there when the fence was built. They don’t know to what reason it was built, but there definitely was an intent, because no crazy person makes a fence for no reason.

‘So, there is this gap of knowledge about the reasons why certain policies exist in organizations. In most bureaucracies, we trust that we should have all these policies. If I inherit a bunch of policies of my predecessors, I tend to keep it, adding my own policies to it to simply move on. That’s bureaucracy: it keeps compounding.

‘In the private sector, you have founders and long-term tenure players who know where the bodies are buried. They see legacy build up. They see the market forces and hold the ripcord more often. They also tend to force change a little more often. Not as often as I would like, but more often than in public organizations.’

Why monetary incentives fail

Jean-Marie Bequevort: You refer to biology when you talk about organizations. We now see a resurgence of people with an education in the humanities, like ethnologists or anthropologists, taking the stage in organizational development. What is your view on that?

Aaron Dignan: ‘It is certainly true that anthropology and understanding human beings is critically important in business. If you don't know the latest thinking about how we work, what motivates and drives us, how we communicate and convene as community, you will have a very different approach to policy. Any first-year doctoral student in behavioral economics can tell you that we are super-irrational, and that motivation is very complex. If you put bonuses and monetary incentives into a system, you screw it up. Peoples' wiring goes bad! They lose their intrinsic motivation. That is not a good idea. Yet, 99 percent of all public businesses have massive bonusses and incentive structures. That just tells you there is very little human science in leadership and the systems.

‘From the relational side, a huge amount of work needs to be done to understand what makes us feel whole, loyal, psychologically safe and part of a system that creates trust. There is a lot of softer science that matters more than ever. Especially in a world where we more often work remotely and do not have the benefit of body language as much and we do not have the benefit of lasting relationships. I would love to have a lot more diversity of thoughts and diversity of backgrounds in organizations. Diversity is one of those things that in complexity drives positive outcomes. Almost inherently.’

The battle of our time

Jean-Marie Bequevort: You are about to release a new book called Brave New Work. If you fast-forward fifteen years into the future, what will be the characteristics of work? What will be the impact of automation and robotics?

Aaron Dignan: ‘Honestly? I think that is a huge question mark. Our generation of leaders is going to determine that in the next five to seven years. It could go a few different ways. It could go the way of late stage/advanced/crony capitalism combined with automation/robotics and IA, where we have a massive amount of innovative quality. Where we have very automated, extractive global organizations that look like Amazon, but almost no vibrancy in the ecosystem. We would then follow the trend of creating maximally competitive global platform businesses that imply fewer people and make more money for a certain few. That is a possible future.

‘The other way is that we really return to our roots in terms of cooperatives and connections and employee-owned organizations, moving back to an environment where we try to create sustainable, local success. That does not mean we don’t have big platforms, but it means that the big platforms are built differently and are owned differently.

‘What I would like to see is more autonomy, more transparency, more participation. By participation, I mean both in the day-to-day decision making and governance of business and more participation in the economic outcomes of the business than we see today. There are signs that it is happening. In the US, you have public benefit corporations, B Corporations. You got what Eric Ries is doing with the long-term stock exchange where people that hold shares for longer have more votes, to eliminate all the short-term piracy that is going on.

‘To me that is the battle of our time. I don’t think we can solve the macro problems on the level of the political system, the environment, inequality without going in the direction of more participation and more autonomy. If we go the other route, those problems will only be solved for a few people and not for the rest of us. I think it is a coin task.’

You are not just a thoracic surgeon

Jean-Marie Bequevort: In our company we have a very large population of young people and starters. If you would just start working, what would you do to shift the balance into the right direction?

Aaron Dignan (laughs): ‘The first thing you can do as a young person is decide what your values and principles are. Newer generations would love their work to be more meaningful work and make more impact but is very easy to be seduced by traditional institutions. The places that hire you right out of school or MBA are the places that are going to continue the status quo. If there is a recruiter at you event: that is not the play. One choice you have to make is the tough choice of life. Go find an employer who is more of a network model, more egalitarian, more disruptive, who is more focused on autonomy and community success. Do the extra work to find that opportunity and maybe take the pay cut that that requires.

‘The second thing is more about protecting ourselves from what is coming. I talk about the difference between complicated and complex. Basically, “complicated systems” are things like watches and engines that can it can be predicted and fixed by an expert. “Complex systems” are things like weather and traffic, that are surprising and emergent.

‘The tasks that we do at work fit in one of three categories usually. Simple, complicated or complex. I advise young people to pay strict attention to their mix of tasks. The accountabilities they hold. How many of the accountabilities they hold are complicated and could be automated by robots or an algorithm? If you can write the instructions down for how to do it right every time: “Stop doing that thing!” Find a role that does not involve that or modify your role and move in the direction of the complex work. Because the complex, problem-solving, judgement-oriented creative work is the only work that is going to be left. For a young person, it is really important to keep an eye on that all the time. If you talk to your bosses about what assignments you want next, move into the direction of complex assignments.’

Jean-Marie Bequevort: Obviously, the network-based organizations seems to be the model of the future.

Aaron Dignan: ‘For a lot of reasons it is. Most importantly, because we capture our full potential as a system when we use all of our skills in more modular ways. If I say you can only hold one job at the time and that job has a fixed job description, then I am eliminating all the parts of you that make you “you”. That make you wonderful. You are not just a thoracic surgeon. You are not just an auditor. You have other skills. So, better to think about work as a set of project and role mixes. As a market place where people can constantly add roles, take away roles, take on projects, lose projects. Doing that, you create a marketplace inside the organization, just like it’s a marketplace outside the organization. It is a super-efficient way to get all of everybody's gifts on the table.’

Organizational debt

Dirk van Bastelaere: Aaron, you have written an article on how organizations can eliminate their organizational debt. Can you explain the concept first of all, and tell us how to remedy?

Aaron Dignan: ‘Organizational debt is any policy or practice that no longer serves us. There are two major sources of organizational debt in the world. One is the knee-jerk reaction to something that went wrong or right. With people reacting like: “Oh that worked,” or “That didn’t work”. Let’s now quickly bind the system with a policy or process that will make the thing that we want to happen again, happen again. Or that will make the thing that we don’t want to happen again, not happen again.

‘The other source is totally sufficient robust policy that gets out of date and is never reconsidered. Which is much more common in fact. What I like about the model of technical debt in software development is that they matured that thinking around that a lot. Technical debt was boiled down to saying that decisions equal debt. Making decisions when you are developing software you are setting in motion patterns and structures that you later on will be frustrated about. You will be mad that you chose a certain platform. You will be mad you wrote that API, because you will have to go back and redo it.

‘So, it’s important to never make a decision until the last possible moment. Never bind a system unless you have the maximum amount of data that you can afford. Always try to balance between “Do I have enough data to make policy?” and “Would waiting a little bit more be safer?” That’s why I often talk about as it as a “Minimum Viable Policy”, just like an MVP in product. What is the leanest amount of policy that we can hold that will keep us safe, but not inhibit us from innovating.’

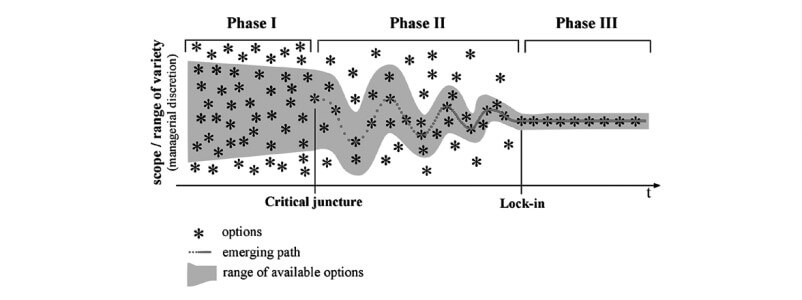

Dirk van Bastelaere: How does organizational debt relate to path dependence? Organizations grow, build, invest, make choices but twenty years later, they suddenly realize the choices that were made have caused a reduction of managerial scope, making the the firm completely dependent on the path they chose to get where they are.

Aaron Dignan: ‘It is a potential expression of debt if the path dependence you created is not working for you. If it is serving you, then that is positional power. You have captured the high ground and you are holding it. When it stops to serve you - if you are Nokia after the iPhone came out – then the fitness landscape (the relationship between the context and all the potential competitors) has changed and you find yourself sitting on a mountain of debt.

‘That’s is one of the reasons why continued divergence is so important, because you are always launching new ships and most of them will fail, but you create the potential platforms that may capture other ground in the fitness landscape. I totally agree. It’s probably is one of the biggest issues in corporate strategy. It’s the sunk cost fallacy, right? Since we’ve spent this much on the status quo, I guess we better keep going.

Jean-Marie Bequevort: I think we got some great insights here. Thank you for the conversation.

Related content

-

Article

Restoring stability after a challenging ERP transition at SEB Professional

-

Article

Building a scalable financial backbone for pan-European growth at Macadam Europe

-

Article

AI in the boardroom: From pilot to priority

-

Article

Data Strategy and Data Management: Two prerequisites for Data-Driven Finance

-

Article

How data management enables faster, better decision-making across the organization

-

Reference case

Power BI drives a reporting transformation at a global industrial group